Ethical principles (e.g., autonomy, nonmaleficence, beneficence, justice, and veracity) present a challenge in case management practice, not any different than those presented to other healthcare professionals. However because of the key role you play as a board-certified case manager (CCM) in the management, coordination, facilitation, and evaluation of the care and services clients/support systems receive, it makes you more likely than others to identify and address ethical conflicts and dilemmas.

Case managers must be astute at aligning their practice behaviors and decisions to accommodate the obligations embodied in ethical principles and standards – specifically those in the CCMC’s Code of Professional Conduct for Case Managers.

Case managers must be astute at aligning their practice behaviors and decisions to accommodate the obligations embodied in ethical principles and standards – specifically those in the CCMC’s Code of Professional Conduct for Case Managers.

This section analyzes and comments on the heart of the Code of Professional Conduct for Case Managers: the standards. Because certain of these standards differ only slightly among one another, some will be coupled and discussed together with special emphasis given to the intent of the various standards, how case managers can adhere to them, and how they could potentially violate them.

The following commentaries are based on the 2015 revision of the Code of Professional Conduct for Case Managers.

The Advocate

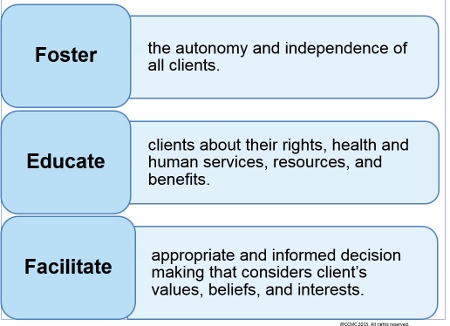

The Code expects that CCMs “will serve as advocates for their clients” (CCMC, 2015, p. 7) and clients’ support systems. Through advocacy, case managers ensure the:

- Completion of a comprehensive assessment that identifies the client’s needs and preferences

- Identification of options and provision of choices for necessary services, treatments, and interventions to the client/support system, when available and appropriate

- Access to healthcare resources that meet their clients’ individual needs

Commentary — This advocacy standard captures the ethical identity of case managers in that they “will serve as advocates for their clients.” This unambiguous wording doesn’t say that case managers “should consider” or “think about” serving as a client advocate – rather, they will do so. You cannot disavow your advocacy role and responsibilities toward the clients/support systems you serve.

If you are asked, “Of what does that advocacy consist?” you can answer that it encompasses all case management practices in accord with the standards of professional conduct as described in the CCMC Code, as well as with the principles, rules, and scope of practice found in the Code.

Furthermore, the Scope of Practice for Case Managers: Underlying Values section of the Code emphasizes that CCMs are to use case management as a “means for improving client health, wellness and autonomy through advocacy” (CCMC, 2015, p. 4).

Three Effects of a Case Manager’s Advocacy

Advocacy in case management is fundamentally other-regarding and client empowering. As much as possible, your advocacy consists of enabling clients/support systems to navigate their world according to their values, beliefs, culture, and interests.

The CCMC strategy for accomplishing that is by your performing an assessment and providing options for necessary services as well as expeditious access to resources to meet clients’ needs.

This means that if you fail to perform an appropriate assessment or to provide the client with service options and access to resources in instances in which doing so is required by case management standards of care, you are failing your advocacy responsibilities, and therefore clients or their representatives may file ethical complaints with CCMC against you as a board-certified case manager.

If a client, then, complains to the CCMC Ethics Committee that you have not helped, will you at least be able to show the committee that you performed a reasonably comprehensive assessment of the client’s needs and that you took steps according to case management standards of care to provide service options and access to resources? Your failing to do this would only corroborate your client’s allegations and might result in formal sanctions.

Representation of Practice, Qualifications, and Competence (S 1, S 3, & S 2)

The CCMC Code of Professional Conduct indicates that CCMs “will practice only within the boundaries of their role or competence, based on their education, skills, and professional experience [and other professional credentials]. They will not misrepresent their role or competence to clients” (CCMC, 2015, p. 7) or clients’ support systems. This refers to the standard of “representation of practice.”

The Code also emphasizes that CCMs will not represent the certification designation (i.e., CCM credential) to imply a depth of knowledge, skills, and professional capabilities greater than those reasonably demonstrated by achievement of certification (CCMC, 2015, p. 7). This reflects the standard of “representation of qualifications.”

Commentary — These two standards are related in that each is concerned with the way you represent yourself to clients, support systems, or other professionals. While the former standard is more concerned about the actual case management practice behaviors, the latter seems more concerned with the claims that you make about yourself to clients and other professionals.

How you interpret competence is important in adhering to these two standards. In fact, CCMC describes in this section of the Code what it means by competence and refers to it as your responsibility. It goes on to indicate that competence “is defined by educational preparation, ongoing professional development, and related work experience” (CCMC, 2015, p. 7).

The Code maintains that in actual practice you must not exceed your professional qualifications. Per the definition of case management, the case manager “assesses, plans, implements, coordinates, monitors, and evaluates” (CCMC, 2015, p. 4) the client’s care program. Importantly, you do not make substantive clinical decisions that authorize that care or its reimbursement.

The “representation of qualification” standard expects CCMs (or a third party) to be truthful in their claims about themselves, especially by way of describing their skill set, the extent of their authority, and the kind of qualifications they bring to meet a client’s needs.

The “representation of qualification” standard expects CCMs (or a third party) to be truthful in their claims about themselves, especially by way of describing their skill set, the extent of their authority, and the kind of qualifications they bring to meet a client’s needs.

You are courting trouble, then, if in the course of your case management practice you step outside your role and undertake or perform a function that is either not in your case manager role or that exceeds your qualifications (e.g., level of training). One example of this can be found below.

Representation of Practice, Qualifications, and Competence

| Case Scenario | Commentary |

|---|---|

|

Suppose June, an independent case manager in private practice, visits a client (Mrs. Wakefield) while in the home and sees that Mrs. Wakefield’s wound dressing has not been changed by the visiting home care nurse. June happens to be a registered professional nurse herself, but has not been practicing in direct nursing care provision for the past 10 years, rather her practice has been limited to case management functions. June might feel more than qualified to change the dressing – but she should realize that in doing so she is arguably stepping outside of her case management role. In the extremely unlikely event that Mrs. Wakefield experiences an untoward event from the wound, June might be held accountable and then find that both her case management malpractice insurer as well as her nursing malpractice insurer balk at covering whatever legal costs might be incurred if she were sued. |

Each insurer can claim that June’s behavior was outside the stipulations of her malpractice insurance coverage – with the case management insurer claiming that she performed nursing measures for which the case management policy was not liable, and the nursing insurer claiming that she provided the services as a case manager and not as a registered professional nurse. June is of the opinion, “It is my obligation to make sure that Mrs. Wakefield is safe and receives quality services at all times while under my care. Ignoring Mrs. Wakefield’s need for a dressing change may be viewed as an act of negligence and may result in a serious infection.” This case illustrates certain adverse (but thankfully unlikely) possibilities of the case manager’s practicing outside the scope of her case management responsibilities. It is likely that June may not have maintained her competence in wound care, considering she had been away from direct nursing care provision for 10 years. Also the continuing education programs she had been attending perhaps focused primarily on case management practice rather than direct clinical care. June in this case is potentially violating the standards of competence and representation of qualifications and practice. |

The “representation of qualifications” standard is also concerned about what you might say or how you represent your qualifications to clients/support systems. Thus, you misrepresent your role if you make statements such as:

- “Mr. Smith does not need a laminectomy procedure.”

- “I will not approve the client’s request to change physicians.”

- “Physical therapy is not indicated for Ms. Anderson after her procedure.”

- “Mr. Greenberg is clearly malingering.”

As case manager, you are not trained in any of the above domains and hence you have no right to make these assertions. You should also be wary of more subtle misrepresentations, such as when a client inquires about the availability of a potential treatment and the case manager says, “No, we can’t allow that.” A more desirable response would be: “I don’t believe your health insurance benefits package includes that treatment as a covered benefit, but let me check first and I will get back to you with a more definite answer.”

The latter statement seems unproblematic, but the former statement implies that you are authorizing coverage. If clients claim – and they sometimes do – you told them that all treatment requests or plans must be approved by you, it might be because you were careless with your language. Even if unintentional, such a misrepresentation might result in a formal sanction from the CCMC Ethics Committee in the event a complaint of an alleged violation is filed.

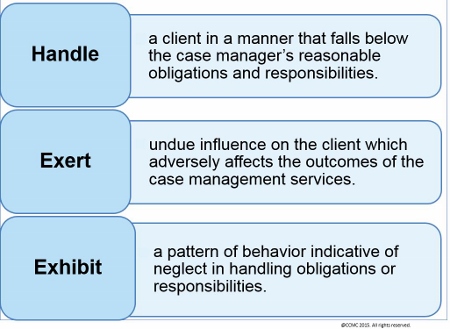

Other aspects of professional responsibility relate to the expectations that you will avoid negligence and therefore will not engage in any activity indicative of neglect.

Acts of Negligence Case Managers Must Avoid

Negligence commonly means a failure to comply with a relevant professional standard. Thus, it is context specific. For example, the airline pilot’s negligence will be different from the lawyer’s, which will be different from a physician’s, which will be different from a case manager’s – since each labors in a different professional domain and deploys different performance behaviors.

Examples include the airline pilot who fails to set the plane’s wing flaps before takeoff; the lawyer who does not file critical documents on time; the physician who writes an erroneous medication order; or the case manager who abandons a client. All depart unreasonably from the standard of care.

To examine whether you are practicing according to ethical standards requires a review of whether or not your behavior met your obligations and responsibilities toward your clients/support systems. If your behavior is found not to have met these obligations, you have risked committing negligence. For example, you may be found negligent if you have failed to:

- Note a clinical finding that is significant for the client’s care, or develop an action plan for the same (for instance, your client is engaging in suicidal ideation about which you do nothing)

- File reports in a timely manner

- Wait to return an injured client to work until their health condition indicated readiness to return

- Exercise objectivity and professionalism in writing reports (e.g., “I feel certain that Mr. Jones missed his physical therapy appointment because he wanted to stay home and drink”)

Typically, when a professional such as a case manager is accused of negligence, one looks to his professional peers to adjudicate the accusation. Peer judgment will inevitably revolve around whether or not the accused acted in a “reasonable and prudent” manner that complied with whatever care standard is at issue.

It makes good ethical sense that your problematic behaviors be evaluated by a representative group of your peers, because that group is presumably in the best position to determine whether an unreasonable degree of departure or variation from the standard of care or practice has occurred.

Case managers and other professionals are not expected to perform at superlative or transcendent levels – rather at the level of an ordinary, similarly qualified individual.

Case managers and other professionals are not expected to perform at superlative or transcendent levels – rather at the level of an ordinary, similarly qualified individual.

The lesson – if you are considering doing something that might be unorthodox or irregular – is to step back and consider how your behavior would be evaluated by your peers. If you don’t know, you might request a consultation with an ethicist at your organization, CCMC, your local case management chapter, or some other similarly qualified group.

Legal and Benefit System Requirements (S 4)

In its Code of Professional Conduct, CCMC states that CCMs “will obey state and federal laws and the unique requirements of the various [healthcare] reimbursement systems by which clients are covered” (CCMC, 2015, p. 7).

Case managers are expected to be familiar with a client’s health insurance benefits plan and procedures; and if not, to seek relevant information that guides practice and ensures adherence to the plan’s expectations.

Commentary — You, like everyone else, are obligated to obey the law. Failure to do so, especially leading to a criminal conviction, can result in the loss of your CCM credential as well as loss of your primary professional license (e.g., nursing, social work).

This standard serves as a reminder to be intimately familiar with state and federal laws as they apply to health benefit coverage and other reimbursement policies. Health insurance coverage of benefits and their applicable regulations can, of course, differ from payor to payor and state to state.

If you are unaware of the specifics, do not know where to obtain accurate information, or erroneously believe that coverage is available when it is not, you are practicing with an inadequate knowledge base and – at least in the former instance – might be sanctioned for fraud.

Lack of knowledge of a client’s health insurance and benefits plan limits a case manager’s ability to advocate for the client/support system, and therefore, risks an ethical violation to the CCMC Code of Professional Conduct.

Lack of knowledge of a client’s health insurance and benefits plan limits a case manager’s ability to advocate for the client/support system, and therefore, risks an ethical violation to the CCMC Code of Professional Conduct.

Use of the CCM Designation (S 5)

This standard as described in the Code pertains to the designation of board-certified case manager or “Certified Case Manager” (CCM) and states that the CCM initials “may only be used by individuals currently certified by the Commission for Case Manager Certification [and remain in good standing]. The credential is only to be used by the individual to whom it is granted, and cannot be transferred to another individual or applied to an organization” (CCMC, 2015, p. 7).

Commentary — If you have not achieved the CCM designation but sign “CCM” after your name, you are violating CCMC’s ethical standards and committing fraud. This will result in CCMC’s issuing a “cease and desist” order upon discovery.

Consider a case in which it was discovered that you had been using the CCM designation prior to formally having achieved it. When asked why you had been using the designation without justification, you replied that your employer had told you that it was acceptable to do so since you had already sat for the certification exam even though the result was still pending.

In this case you could be stripped of your CCM credential permanently. It could be argued that – as the CCM designation implies a considerable skill and knowledge attainment – individuals who use the credential illicitly commit an act of fraud.

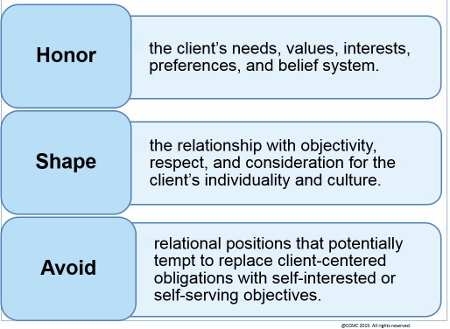

Conflict of Interest, Objective Relationships with Clients, and Dual Relationships (S 6, S 10, & S 19)

The CCMC expects board-certified case managers to “fully disclose any conflict of interest to all affected parties, and… not take unfair advantage of any professional relationship or exploit others for personal gain. If, after full disclosure, an objection is made by any affected party, the Board-Certified Case Manager (CCM) will withdraw from further participation in the case” (CCMC, 2015, p. 7).

The Commission also asserts that CCMs will:

- “maintain objectivity in their professional relationships”

- “not impose their values on their clients” and support systems

- “not enter into a relationship with a client (business, personal, or otherwise) that interferes with that objectivity” (CCMC, 2015, p. 8).

Avoiding Conflict of Interest and Maintaining Objectivity

Healthcare professionals – and you are no exception – who enter into situations that pose a “conflict of interest” attract considerable and almost always undesirable attention.

Conflicts of interest may occur in a myriad of ways. Healthcare researchers, for instance, sometimes have an equity interest in a medical drug or device whose investigation they themselves are conducting. To the extent that they report favorable findings regarding the effectiveness of the drug or device, they may profit financially. These individuals are certainly conflicted. It is easy to see how the lure of profit may overwhelm their ethical obligation to conduct and report their findings objectively and truthfully.

The case manager who can steer business to a family member may violate the “conflict of interest” standard; while one who delivers case management services to a family member risks losing his/her “objectivity.”

The case manager who can steer business to a family member may violate the “conflict of interest” standard; while one who delivers case management services to a family member risks losing his/her “objectivity.”

If you are involved in instances such as these, you are obligated to two parties whose interests do not necessarily coincide. Disclosing the existence of this dual relationship honors the client’s autonomy. Armed with that information, the client can then – at least theoretically – determine whether he/she:

- Desires to work with the case manager,

- May wish to share certain important information with the case manager, and/or

- May decide to withhold certain information that is sensitive in nature.

The CCMC Code requires you to resist unreasonably imposing or insinuating your own values and interests into the clients’ informed decision making. You:

- Can certainly make recommendations to your clients/support systems, as long as those recommendations are within the case management scope of practice

- Cannot insist that your clients must adopt what you recommend for the case management plan of care, and certainly cannot threaten your clients if they choose to do otherwise

Conflict of interest may arise in contexts of dual relationships. Disclosure in these situations promotes your adherence to these ethical standards.

Violation of “Dual Relationship” Ethical Standard Example

| Case Scenario | Commentary |

|---|---|

|

Mr. Jenkins is a workers’ compensation case manager who feels a more intense allegiance to a third-party payor than to the payor’s beneficiaries. Mr. Jenkins knows that the sooner he returns an injured employee to work, regardless of whether this employee is medically or functionally ready, the more he ensures continuing business from the employer, who in turn is interested in saving healthcare costs. |

Mr. Jenkins in this case is risking an ethical violation when he prioritizes his interest in continued business from the employer above the risk of harming and wronging the injured employee. The dual relationship is that although the case manager is obligated to advocate for the client/support system, he/she is being paid by the client’s insurer, whose healthcare cost-saving objectives might run counter to the client’s accessing services to which he/she is entitled and needs. To avoid violating the ethical standard for dual relationships, Mr. Jenkins is expected to disclose his relationship with the client’s employer or insurer and have a transparent conversation that allows the client to express any concerns he/she may have. |

As much as you may find the challenge of dual relationships concerning, you should nevertheless know that some of your clients who have been injured on the job may:

- Not believe their employers have their best interests at heart

- Potentially perceive you as an instrument of the employer

- Potentially have concerns that you are not a true client advocate

When you remark to your clients/support systems that your role is to support and advocate for them, you are then required to see your promise through and abide by ethical standards that obligate objectivity, transparency, and advocacy.

If you are working with clients who also happen to be your employers, employees, friends, relatives, and/or research subjects, you must avoid “role boundary violation”; you must maintain objectivity when taking on clients who play a significant role in your life (i.e., an employee, friend, or relative).

- Presumably, these clients will know that you are performing case management functions but, because of the intimacy of your relationship, they may harbor expectations or impose them on you, either of which can turn troublesome.

- Alternatively, you might believe you owe more or should be willing to do more for a client who is a friend or relative than for the client who is a stranger.

These kinds of situations are not uncommon in healthcare – such as the physician who treats a family member – but they can turn troublesome when expectations are not met or questioned.

It is probably best for you not even to enter such problematic situations if you can help it or, if you do enter them, to proceed transparently as the ethical standards of the CCMC Code of Professional Conduct suggest.

Reporting Misconduct (S 7)

One of the professional responsibilities of case managers is to report misconduct (e.g., sharing confidential information about a client with those not authorized to have it) of fellow case managers to:

- Superiors at the place of employment, following the chain of command

- CCMC if the case manager holds the CCM credential

- Other professional bodies (e.g., state licensing boards) authorized to investigate or to act on such actions or violations

The Commission, in its Code of Professional Conduct, states that “anyone possessing knowledge not protected as confidential that a Board-Certified Case Manager (CCM) may have committed a violation as to the provisions of th[e] Code is required to promptly report such knowledge to CCMC” (2015, p. 7).

Commentary — The ethical intention behind this standard occurs in practically every code of professional ethics: Licensed or certified professionals have an obligation to police their own actions, and to take appropriate steps when they notice another professional practicing in a problematic manner. Despite the universality of this obligation, it is also probably one of the most difficult with which to comply.

Calling a foul on others or impugning that they may be practicing in a risky, ineffective, or otherwise problematic manner can create uncomfortable feelings for everyone involved. This however should not stop case managers from their obligation to report professional misconduct.

Calling a foul on others or impugning that they may be practicing in a risky, ineffective, or otherwise problematic manner can create uncomfortable feelings for everyone involved. This however should not stop case managers from their obligation to report professional misconduct.

Should you feel you must say something, you may nevertheless fear that doing so will appear hateful or disloyal and that you may be retaliated against.

The end result of reluctance to do so, however, is that in all probability, the problematic behavior will continue and may ultimately result in significant harm to either clients/support systems or other fellow professionals.

The complexity of reporting professional misconduct is too broad a topic to thoroughly discuss here, but it nevertheless bears pointing out that if CCMC expects you to comply with this standard, you have to feel safe in reporting misconduct. To the extent you believe that your good intentions bring you grief, adherence to this standard is unlikely.

If you feel compelled to report misconduct, you should ensure that your claims are robustly supported by good and objective evidence. Ethical standards caution against you making reports that are not factual and warranted. Ironically, even when you have the best intentions, suspicions can often accompany any report of misconduct you make.

Case managers who bring in allegations of misconduct should anticipate that their claims, and possibly motives, will be questioned. Consequently, there is no substitute for ensuring the factual accuracy of these concerns as that accuracy will be the case manager’s staunchest defense should their intentions or motives get questioned.

Case managers who bring in allegations of misconduct should anticipate that their claims, and possibly motives, will be questioned. Consequently, there is no substitute for ensuring the factual accuracy of these concerns as that accuracy will be the case manager’s staunchest defense should their intentions or motives get questioned.

The literature on departures from standards of practice strongly recommends that problematic conduct be nipped in the bud. The more the behavior is allowed to endure, the more the misbehaver will think such conduct is allowable, and the more likely this conduct will continue and become normalized.

While reporting misconduct can seem like one of the most painful things you may do, it is nevertheless an enormously important professional obligation. This act:

- Speaks to the importance of maintaining the public trust

- Is one of the most admirable examples of professionals taking very seriously their obligation to protect people who use their services

Compliance with Proceedings (S 8)

The “compliance with proceedings” ethical standard notes that CCMs must assist in the process of enforcing the Code as directed by CCMC’s Committee on Ethics and Professional Conduct. The committee expects case managers to:

- Cooperate with the inquiries of alleged violations

- Participate with the committee’s proceedings regarding a complaint

- Comply with the committee’s directives (CCMC, 2015, p. 8)

Commentary — This standard seems self-explanatory; however, knowledge of the section of the Code on CCMC Procedures for Processing Complaints (2015, pp. 11-21) is necessary for ensuring adherence. If you participate in investigations and proceedings of complaints concerning alleged violations, you are expected to comply with CCMC’s rules and guidelines. Lack of adherence may result in an ethical violation in the area of “professional misconduct.”

Expectations in the Event of a Complaint of a Code Violation

| CCMC’s Expectations from Board-Certified Case Managers Regarding a Complaint of a Code Violation |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Although it is to be hoped that you will never experience a situation calling for your involvement in a formal hearing or investigation of misconduct, you are encouraged to read this section of the Code. You may be impressed at how careful the investigation process is, and at the numerous considerations and rights protections that are afforded to everyone involved.

Description of Services (S 9)

This standard is important for enhancing the case manager-client relationship. It states that CCMs will provide information to clients about case management services, including a description of:

- Services

- Benefits

- Risks

- Alternatives

- The right to refuse services

- Cost of case management services prior to initiation, where applicable (CCMC, 2015, p. 8)

Commentary — Description of services is especially important because it allows clients/support systems to make informed decisions about and consent for case management and other services.

While it seems self-explanatory, you may nevertheless wonder how much and what kind of information clients need to make autonomous decisions about case management.

One may determine what information is needed and necessary for making informed decisions by asking what kinds of information are material to the client’s judgment, as in “If the client knew this, would it figure prominently in his/her decision to accept or refuse case management services?”

One may determine what information is needed and necessary for making informed decisions by asking what kinds of information are material to the client’s judgment, as in “If the client knew this, would it figure prominently in his/her decision to accept or refuse case management services?”

While you may believe that the benefits of case management services significantly outweigh any accompanying burdens, some clients may not desire the involvement of case managers. These clients may be wary about sharing medical and health information or anything pertaining to their histories with those whom they perceive as strangers.

In workers’ compensation cases, for example, clients may distrust you on the basis of stories they have heard from coworkers who may not have had a desirable experience with the case management process.

This standard specifically addresses the client’s right to refuse services, in other words, his/her right to say “no.” This refers to the expression of autonomy. A client saying no can be unsettling to the case manager as it is a refusal of their services when they know how beneficial case management may be to the refusing client.

Feelings of rejection aside, to the extent that a client adequately understands the informational content of the case manager’s disclosure and still rejects case management services, the case manager must respect that decision even if she/he believes it profoundly unwise.

Feelings of rejection aside, to the extent that a client adequately understands the informational content of the case manager’s disclosure and still rejects case management services, the case manager must respect that decision even if she/he believes it profoundly unwise.

Ultimately, clients/support systems have the right to make both wise and unwise decisions – as long as the clients are competent, can exercise understanding and adequate insight into their decisions, and have some appreciation of the potential liabilities.

Termination of Services (S 11)

This standard states that “prior to the discontinuation of case management services, Board-Certified Case Managers (CCMs) will document notification of discontinuation to all relevant parties consistent with applicable statutes and regulations” (CCMC, 2015, p. 8).

This standard is mostly concerned that clients/support systems and others involved are aware of the need to terminate services before actual termination goes into effect – a right that facilitates transparency and shared decision making.

Commentary — While this standard may seem obvious, it is helpful to reflect on its ethical justification. At the very least, clients/support systems should harbor no false beliefs or expectations about services to which they may no longer be entitled; alternatively they should be notified of the intention to discontinue services, and so have an opportunity to rebut the discontinuation decision.

You obviously can have acceptable reasons to sever your relationships with clients/support systems. Perhaps you can show that a client no longer receives any benefit from case management services so that:

- Continuation of the services is wasteful

- The term of the case management service has officially expired and the client is no longer entitled to case management services

- The client is unable to benefit from services anymore – perhaps because he/she is nonadherent with the treatment or has needs other than what a case manager can reasonably provide

Importantly, however, you cannot abandon the client. Abandonment is understood as the health professional failing to attend to client needs despite the client’s having a continuing right to have those needs accommodated.

When you decide to terminate the relationship with a client but doing so would dispose the client to risk or peril and the client has a continuing right to services, you must arrange for a reasonable substitute. You cannot – legally or ethically – leave the client in harm’s way. Otherwise you could indeed be accused of abandonment. The harm would be compounded if the client’s condition deteriorated from an absence of attention and care.

Legal Compliance and Protected Health Information (S 12 & S 14)

In its Code of Professional Conduct, CCMC emphasizes that CCMs “will be knowledgeable about and act in accordance with federal, state, and local laws and procedures related to the scope of their practice regarding client consent, confidentiality, and the release of information” (CCMC, 2015, p. 8).

The Code also refers to the requirement by law and states that CCMs “will hold as confidential the client’s protected health information, including data used for training, research, publication, and/or marketing unless a lawful, written release regarding this use is obtained from the client/legal representative” (CCMC, 2015, p. 8).

Commentary — The belief that ethics and law are on opposite poles is erroneous. Laws result from a society’s ethical intuitions, such that if the intuitions are well-calibrated and people are ideally motivated, there should be no such thing as an “unethical law.”

The ethical standards of “legal compliance” and “protected health information” point to the need for you to have a good knowledge as to how the law on client consent, confidentiality, and release of information ― especially pertaining to the client’s identity ― applies to your practice.

As has been emphasized all along, your prima facie or “first blush” obligation is to protect your clients’ rights and liberties. Consent honors your clients’ right to control what happens to them; confidentiality, release of information, and revelation of a client’s identity pertain to the client’s right to control what information is known about him/her.

To appreciate these principles, especially as they pertain to confidential information, you should ask yourself how you would want confidential information about yourself to be respected and treated. More likely than not, the more intimate or potentially damaging to one’s interests or goals that confidential information is, the more the individual would want it keenly protected.

Apart from legal regulations, you can remind yourself of two ethical criteria that inform decisions about whether and what information should be released:

- Does the individual to whom the information may be released have a right to it?

- Does the individual to whom information may be released have a reasonable need to know it?

Suppose a client tells you that he is infected with HIV and that no one else knows. How should you proceed?

First, you may well wonder whether or not the client is correct in the claim that no one else knows. Obviously for the client to have knowledge of an HIV diagnosis he would have to have been tested. And depending on whether he was tested at a public clinic, a private clinic, or a federal facility like the Veteran’s Administration, the health professionals involved may (or may not) have been legally required to disclose this client’s HIV status to some public authority like the Department of Health. So the client may be wrong to assume that no one else knows. But – for the sake of this hypothetical scenario – assume he is correct, and that only he and you know of his HIV status.

In the 1980s the United States was gripped with HIV hysteria, and many thought it necessary to have the identity of everyone infected revealed. Later those involved realized that knowing who had the virus was hardly a guarantee against what should have been their chief concern: How did health professionals and society at large contain the spread or transmission of the virus?

Your knowing that your next-door neighbor is infected with HIV does virtually nothing to curtail the transmission of the virus. The ethical concern confronting you as case manager, then, should be along the lines of “What harm does this virus pose to my client or to others with whom my client can come into intimate contact?”

For example, if your client is sexually intimate with others, does his/her partner(s) know of the HIV status? Georgia law, for example, makes it a felony for an individual with HIV to engage in sexual intimacy with another without informing that other of the positive HIV status (see OCGA § 16-5-60[c]).

The case manager’s advocacy responsibilities would at least require her to make her client aware of the law regarding HIV status.

The case manager’s advocacy responsibilities would at least require her to make her client aware of the law regarding HIV status.

If you are dealing with a client who is sexually intimate with another, should you contact the intimate partner and reveal your client’s HIV status? You might think it a rare occurrence for case managers to inform sexual intimates of their clients’ HIV status for the simple reason that such disclosure would normally fall to the client’s physician. However – in the interest of client advocacy – if the client’s physician is unaware of the client’s HIV status, he/she seems to have a need to know so as to be able to care for this client effectively. Ultimately, the client’s physician is best poised to handle the management of this individual’s HIV and its disclosure to others.

Nevertheless, you should first discuss all this with the client, discern his/her preferences, and secure his/her consent to disclosure. Clearly the client has a right to keep this information secret, even from his/her health professionals, although the client should be compassionately made aware that:

- The sooner the client receives treatment, the better his/her quality of life will be

- The client’s belief that he/she can conceal HIV status from involved health professionals indefinitely is doubtful

Consider another situation: You are working on a workers’ compensation case and you decide to contact an ethicist, stating that you received medical records from the physician’s office of the injured worker which inadvertently revealed to you that the client is infected with HIV. You are wondering whether or not to inform the client’s employer.

After some reflection, the ethicist advised that the client’s HIV would not pose a hazard to anyone at the client’s job – since the client did not expose his blood products to anyone there – nor did it interfere with the client’s job performance. Therefore, the client’s employer had no need to know it, and you had no duty to reveal it (which you did not).

If you question this resolution, you should ask yourself, “Whose side should I be on?” If you are truly a client advocate, the Code requirement to maintain confidentiality of the client’s HIV diagnosis seems obligatory. If you are more allegiant to the client’s employer, you may feel more compelled to disclose; however, as a case manager you should be a client advocate first.

Disclosure of Information (S 13)

This standard states that at the outset, CCMs must inform their clients “that any information obtained through the [case manager-client] relationship may be disclosed to third parties, as prescribed by law” (CCMC, 2015, p. 8).

Case managers may disclose client information to clients, payors, service providers, and governmental authorities. This disclosure must be limited to what is necessary and relevant – except where the law requires that case managers reveal certain information to appropriate authorities – as soon as and to the extent that the case manager reasonably believes necessary, to prevent the client from:

- Committing acts likely to result in bodily harm or imminent danger to the client or others

- Committing criminal, illegal, or fraudulent acts

Commentary — This standard could have been included in the standard “protected health information” – particularly since that standard addresses obligations to a client with HIV.

Indeed, all of the previous comments as to whether you are obligated to report such a diagnosis are pertinent here – especially when your reporting concerns the client’s intent to commit harmful acts to himself or others, or to commit illegal acts.

Ultimately your disclosure of your client’s HIV status is an attempt to ensure that your client or others involved are kept safe.

Ultimately your disclosure of your client’s HIV status is an attempt to ensure that your client or others involved are kept safe.

Many aspects of this standard have already been covered under the earlier standards. Important to this standard is that disclosure emphasizes respect for client autonomy and right to self-determination.

You must recognize that when you reveal information about a client to a third party, you lose the ability to control that information. This is one reason why the principle of confidentiality exists.

- If clients believed that their health providers might reveal information to anyone on a whim, many clients would be extremely circumspect about what they would reveal to their healthcare professionals – including you.

- That inhibition might, in turn, compromise the health professional’s ability to care for that client if the professional is without critical information bearing on the client’s clinical situation.

That you may have dual relationships – as speculated in another standard in CCMC’s Code of Professional Conduct – may rightly or wrongly strike many of your clients as important in terms of what information they choose to disclose.

In some instances, it may be more valuable to your clients that some of their personal information remain known only to you rather than being disclosed to other healthcare professionals – no matter how well meaning the latter may be.

Despite the fact that revealing certain private information to health professionals may result in better care and thus count as a good, that very same revelation may prove detrimental to some clients if it results in their losing their jobs, their self-esteem, their relationships, or their health insurance.

Despite the fact that revealing certain private information to health professionals may result in better care and thus count as a good, that very same revelation may prove detrimental to some clients if it results in their losing their jobs, their self-esteem, their relationships, or their health insurance.

Though you may feel that you are entirely on the side of the good and the right, some of your clients may view you differently. Hence, the standard on “disclosure of information” obligates you to share with your clients that you may be contractually, ethically, or legally bound to inform third parties about information the clients/support systems reveal to you.

While this may be an uncomfortable revelation for you to disclose, it is nevertheless in keeping with the advocacy and trustworthiness with which case managers represent themselves to their clients/support systems.

Records: Maintenance/Storage and Disposal (S 17)

This standard notes that CCMs “will maintain the security of records necessary for rendering professional services to their clients and as required by applicable laws, regulations, or agency/institution procedures (including but not limited to secured or locked files, data encryption, etc.)” (CCMC, 2015, p. 9).

The standard also emphasizes that – subsequent to termination of services and closure of client’s records – case managers will maintain the records “for the number of years consistent with jurisdictional requirements or for a longer period during which maintenance of such records is necessary or helpful to provide reasonably anticipated future services to the client” (CCMC, 2015, p. 9).

The standard additionally explains that when the required time period of maintaining client’s records has expired, “records will be destroyed in a manner assuring preservation of confidentiality, such as by shredding or other appropriate means of destruction” (CCMC, 2015, p. 9).

Commentary — An entire industry has developed around these standards. As medical and health information records have increasingly gone to electronic formats, access to them has become much easier. Our ethical sensibilities about protecting privacy have not changed since those records were in paper form, however. Healthcare professionals must continue to be vigilant about unauthorized access to this information.

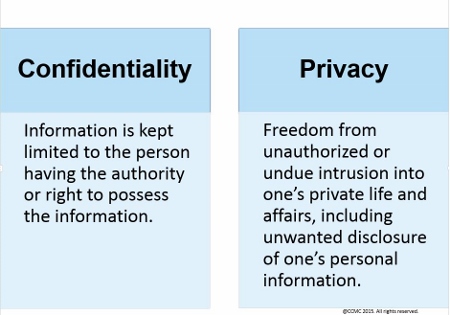

Although this standard focuses on maintaining records in ways that protect the client’s confidentiality, one suspects that the real concern of the standard is about privacy. Privacy and confidentiality are not identical.

Differentiating Confidentiality and Privacy

A breach in confidentiality occurs when you reveal information to someone who is not supposed to have it; a breach that concerns privacy results when you fail to protect confidential information from reaching persons who have no right or need to know it.

Protecting health and medical documents from the prying eyes of unauthorized persons seems to be the primary intent of the standards related to the maintenance, storage, and disposal of records.

Protecting health and medical documents from the prying eyes of unauthorized persons seems to be the primary intent of the standards related to the maintenance, storage, and disposal of records.

Many states have statutes that criminalize unauthorized access to clients’ confidential records. Georgia, for example, states that “any person who uses a computer or computer network with the intention of examining any employment, medical, salary, credit, or any other financial or personal data relating to any other person with knowledge that such examination is without authority shall be guilty of the crime of computer invasion of privacy” (OCGA § 16-9-93[c], emphasis added).

Under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), any entity that creates, receives, manages, or stores individually identifiable health information is subject to the maze of regulations and policies of the act. (See http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/srsummary.html for more information.)

HIPAA specifically requires that such organizations designate and train an individual who will be responsible for privacy policy and procedures. In effect, this person becomes the HIPAA expert who is to be knowledgeable about the privacy regulations on information storage.

Case management practices – no matter how modest their size – should have designated personnel knowledgeable and vigilant about adherence to HIPAA rules.

Case management practices – no matter how modest their size – should have designated personnel knowledgeable and vigilant about adherence to HIPAA rules.

Even more importantly, you need to remind yourself of the enormous importance your clients attach to sensitive information gained about them. Consider the following examples in which you:

- Use your own passwords to illicitly access electronic medical records of clients not under your care – only because you are “curious” about a particular client. (See, for example, Yath vs. Fairview Clinics, 767 N.W.2d 34 [2009].)

- Send a client’s health records inadvertently and mistakenly to the wrong parties.

- Share the wrong client’s health records with other parties.

The above examples are breaches of privacy because they fail to shield and protect sensitive client information according to ethical and legal norms.

The storage and maintenance of sensitive health information requires your continuing commitment to remain abreast of privacy rules as well as ways they might be breached, such as by hackers. Furthermore, and even if you are insensitive to your ethical obligations involving privacy, you should realize that unauthorized breaches of sensitive medical information can be subject to criminal prosecution and heavy penalties.

Although not advisable, you may sometimes need to electronically record your communications with clients/support systems.

When you are unable to avoid electronic recordings, you have a duty to inform your clients about the recordings in addition to securing beforehand the client’s written permission (authorization) to record.

Electronic Recordings of Communications with Clients

| Sample Questions Case Managers Must Answer to Clients about Electronic Recordings |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The client’s autonomy-based rights require your responding to these questions honestly. Indeed, you should think of this standard as requiring “informed consent” to audiotaping client communications, and permission of the client prior to sharing of the recording with other parties as similar to “written release of information.”

Reporting and Testimony (S 16 & S 18)

The Code of Professional Conduct states that CCMs “will be accurate, honest, and unbiased in reporting the results of their professional activities to appropriate third parties” (2015, p. 9) and avoid unduly influencing the decision-making process.

The Code also expects CCMs “when providing testimony in a judicial or non-judicial forum… [to] be impartial and limit testimony to their specific fields of expertise” (2015, p. 9).

Commentary — Both of these standards remind you of the considerable influence you can exert in planning and coordinating the courses of care for your clients/support systems. Therefore, you are expected to be judicious and to perform your duties according to your scope of practice and qualifications.

Case managers must be extremely careful about their use of language – especially in reports – and must refrain from sounding subjective, opinionated, judgmental, or biased.

Case managers must be extremely careful about their use of language – especially in reports – and must refrain from sounding subjective, opinionated, judgmental, or biased.

In some situations, remaining objective can be challenging – such as in situations in which you do not like the client/support system, or suspect the client is trying to take advantage of the situation at hand. Yet consider the following examples:

- You suspect that the client was inebriated when you last were together. You may note that “Mr. Jones’ speech was slurred, his eyes appeared glassy, his gait was unsteady, and his breath suggested alcohol, although I cannot be certain” (rather than say, “Mr. Jones was drunk when we last met”).

- You write in your reports that “the injured worker was exaggerating his pain,” or “The injured worker was reported hanging Christmas lights from his roof,” or “The client’s wife is obnoxious and argumentative.”

Even a modestly skilled attorney will make you regret these representations – largely because they are speculations, they constitute claims that you have no qualifications to make, or they present a degree of bias that gives the impression you are compromising professional judgment.

You should recognize that both law and ethics expect you always to exercise your professional objectivity and never allow any unfounded hunches or assumptions that are especially colored by your likes and dislikes to interfere with your practice. And of course you are expected to advocate for your clients, which implies that you will always be reasonably supportive of them.

Although it is perfectly understandable for you to experience feelings of frustration, disappointment, and even rage toward certain clients, you must never express those sentiments within the professional compass of your work. Indeed, you should be very careful of sharing them even with intimate acquaintances because once you do, you lose control of those representations and cannot predict who might learn of them.

Unprofessional Behavior (S 20)

The standard states, among other things, that it is unprofessional behavior if the CCM:

- commits a criminal act

- engages in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit, or misrepresentation

- discriminates against a client because of race, ethnicity, religion, age, gender, sexual orientation, national origin, marital status, or disability/handicap

- engages in sexually intimate behavior with a client; or accepts as a client an individual with whom the case manager has been sexually intimate (CCMC, 2015, p. 9)

Commentary — You may develop a marked affection for certain of your clients. Should that happen, you need to be cautious about your professional distance. If you are not – and stories are common about professional colleagues who wind up marrying a client – then you should cease your professional relationship with the client and refer him/her to someone else for care.

When case managers are unable to separate their professional and personal roles toward clients/support systems, they are at increased risk for violating their professional role boundary.

When case managers are unable to separate their professional and personal roles toward clients/support systems, they are at increased risk for violating their professional role boundary.

There are less dramatic instances than romance, of course, which can nevertheless also be problematic. You might become very friendly with a client or take on a client who is already a personal friend. Whenever you begin “mixing” or combining role-relationships, you are courting trouble.

For example, your conversation – especially regarding sensitive topics like politics, religion, and what you find humorous or entertaining – is one thing with friends, but should be quite different (and perhaps value neutral) with professional clients.

When a friend or acquaintance becomes a client, these role-related behaviors can blur. Confusion can reign over what one individual has a right to expect from the other. Even something as seemingly innocuous as giving a client a ride to his/her therapist’s clinic can be problematic.

When a friend or acquaintance becomes a client, these role-related behaviors can blur. Confusion can reign over what one individual has a right to expect from the other. Even something as seemingly innocuous as giving a client a ride to his/her therapist’s clinic can be problematic.

As much as you may enjoy and feel fondly toward certain clients, you should always maintain a professional distance that enables you to execute your job responsibilities efficiently and objectively.

The psychological and relational repercussions of disrespecting professional boundaries can prove extremely regrettable. It is important to identify learning opportunities and learn from the events you become aware of. Once learned, they are unlikely to be forgotten.

Fees (S 21)

The Code of Professional Conduct states that CCMs “will advise the referral source/payor of their fee structure in advance of the rendering of any services and will also furnish, upon request, detailed, accurate time and expense records. No fee arrangements will be made that could compromise health care for the client” (2015, p. 10).

Commentary — This standard makes good business sense in that there should be no surprises over your collecting reimbursement for services rendered. Thus, your fee structure should be clearly delineated to the payor before services begin, and billing for case management services should occur in a timely manner.

The case manager who realizes, for example, that a particular case is going to require more attention and more time than was originally anticipated should report such to the payor before committing any additional energies and risking subsequent complaints from the payor about being overcharged.

The case manager who realizes, for example, that a particular case is going to require more attention and more time than was originally anticipated should report such to the payor before committing any additional energies and risking subsequent complaints from the payor about being overcharged.

You must not succumb to any unpleasant feelings you may have over discussing your fee structures because your neglecting to do so may precipitate more uncomfortable feelings later on, when your employer balks at paying those fees.

How may a fee arrangement potentially compromise healthcare services for the client? Consider an employer offering to pay you a bonus:

- If you return an injured employee to work before the employee’s official return-to-work date;

- On the basis of how much money you save an insurer on healthcare costs; or

- For “steering” clients to certain treating health professionals whom the insurer approves and away from professionals whose services or programs of care the insurer deems unreasonably expensive.

Obvious ethical concerns emerge. Your clients may be getting less than they deserve because of the way a bonus plan can mask your professional judgment. Your making extra income as a result of reducing the amount of care clients receive inevitably arouses ethical and legal suspicions.

Ethical and legal concerns arise in these examples because of the “other-regarding” nature of ethics and your advocacy obligations. To the extent that you act according to your personal self-interests and, in so doing, risk harming others – especially others to whom you have ethical obligations – you act unethically.

Advertising (S 22)

The ethical standard of advertising explains that such must be done “in a manner that accurately informs the public of the skills and expertise being offered. Descriptions/advertisements by a Board-Certified Case Manager (CCM) will not contain false, inaccurate, misleading, out-of-context, or otherwise deceptive material or statements. If statements from former clients are used, the Board-Certified Case Manager (CCM) will have a written, signed, and dated release from these former clients. All advertising will be factually accurate and will not contain exaggerated claims as to costs and/or results” (CCMC, 2015, p. 10).

Commentary — In the United States, case management occurs in an extremely competitive marketplace such that hyperbolic statements like the ones listed below appear frequently.

- “We Guarantee Results”

- “Where Excellence Is the Norm”

- “Where Miracles Happen”

- “The Best Trained Personnel”

- “The Most Popular Treatment Facility”

If you make such claims, you should be able to justify them with good data or no reasonable person will take you seriously. Further, if a clinic boasts that its case management staff is “The Best Trained in Wallapalooza County” but there is no other clinic in Wallapalooza County, the claim is deceptive and disrespectful to potential consumers.

Until only a few decades ago, physicians in particular frowned on doctors advertising their services. Yet you might argue that not only is there nothing inherently wrong in advertising, it also promotes a social good: informing healthcare consumers about available services.

Effective, well-oiled marketplaces depend on robust competition. Service providers who are unknown erode marketplace efficiency. It is difficult, then, to argue against the right of professionals to advertise, as long as they subscribe to the stipulations of this standard.

False advertising is a fraudulent activity and violates the various case management standards that insist on honesty, accuracy in representing services, and respecting client autonomy.

False advertising is a fraudulent activity and violates the various case management standards that insist on honesty, accuracy in representing services, and respecting client autonomy.

Case management clients cannot make good decisions when they are deprived of necessary information or are offered false information. Indeed, even if you wish to use a client testimonial, that testimonial should reflect a reasonably familiar experience rather than one that is extremely unusual. Consider the example of advertisements for weight reduction interventions, which frequently use client testimonials but almost invariably note that “individual results vary” or that “these results are unusual.”

The case management firm whose client makes a remarkably spectacular recovery should think twice about using his/her testimonial, unless the firm believes that it can reliably replicate that result.

The advice to “underpromise and overdeliver” seems preferable to its alternative, especially considering the economic necessity of securing returning business. If a case management practice flourishes but with markedly inferior outcomes compared to its competitors, you might suspect the ethical nature of its underlying business arrangements.

Solicitation (S 23)

The Code highlights in the standard for solicitation that CCMs “will not reward, pay, or compensate any individual, company, or entity for directing or referring clients, other than as permitted by law and/or corporate policy” (2015, p. 10).

Commentary — Nothing contained in this standard precludes you from making reasonable expenditures in entertaining individuals who have referred or may in the future refer clients to you, or from giving gifts of minimal value to such individuals.

The point of this standard, however, is that undue payments made for client referrals disrupt the ethical as well as economic objectives of just delivery of healthcare services to clients.

The case management agency that pays referral sources for clients might survive as a business but for an unethical reason: Rather than reaping referrals on the basis of good service, the agency simply bribes referral sources. The quality of the agency’s work, which should rightfully be pivotal in ensuring its success, drops out of the equation.

Unethical solicitations theoretically drive up the cost of business. The case management agency that solicits business through bribes for referrals must presumably recover the costs of those solicitations by either increasing its rates or by reducing services.

Unethical solicitations theoretically drive up the cost of business. The case management agency that solicits business through bribes for referrals must presumably recover the costs of those solicitations by either increasing its rates or by reducing services.

When the case management agency either increases its fees or reduces its services, the clients it serves lose out; while as a matter of ethics, the clients should be the primary beneficiary of a marketplace operating according to sound ethical and economic principles.

It comes as no surprise, then, that when such solicitations are uncovered and those of such practice are prosecuted, the penalties can be harsh and the embarrassments memorable.

You must be careful about accepting gifts from your client. This may present you with the problem of the “gift relationship,” in which X receives a gift from Y, and then X may feel some obligation to return the favor. There is a fine line here that you may end up crossing over into unethical practice, even if you have not intended to.

The return favor may put the client at a disadvantage, because now his/her referral to the professional becomes a means to an end. In other words, the client is “used” to repay the original gift, which is antithetical to client-centeredness and client advocacy.

Substantial literature emphasizes that even though professionals receiving a gift disavow that the gift influences their treatment and referral decisions, research shows that it does. Thus, numerous university teaching hospitals have literally banned pharmaceutical representatives from their campuses in an attempt to assure the objectivity of healthcare professionals against the traditional gift-giving practices of the pharmaceutical industry.

Although CCMC’s Code refers to what is permitted by law or under corporate policy rather than specifying an acceptable gift amount, some practical guidelines have suggested $50 as a maximum amount, but other guidelines forbid professionals from accepting any gift or gratuity from a private individual or firm altogether.

Research: Legal Compliance and Subject Privacy (S 24 & S 25)

The CCMC Code of Professional Conduct addresses research in two standards that concern compliance with research-related laws and privacy of research subjects. The Code states that CCMs:

- “Will plan, design, conduct, and report research in a manner that reflects cultural sensitivity; is culturally appropriate; and is consistent with pertinent ethical principles, federal and state laws, host institution regulations, and scientific standards governing research with human participants” (2015, p. 10).

- “Who collect data, aid in research, report research results, or make original data available will protect the identity of the respective subjects unless appropriate authorizations from the subjects have been obtained as required by law” (2015, p. 10).

Commentary — A review of the ethics of research design is impossibly broad to cover in this section; therefore, you are advised to refer to the following as sources of important information on the subject:

- The Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects, known as the Common Rule (Title 45 CFR part 46 of the Code of Federal Regulations), which governs human subjects research

- The National Institutes of Health

- The Office of Human Research Protections

- University websites of those with research missions

Research that is supported by federal funds – or that is approved by federal entities such as the Food and Drug Administration – must comply with the regulations stipulated in the Common Rule.

Virtually any research that is supported by public or private funds will require oversight by an Institutional Review Board – whether it is commercially operated or at some healthcare organization or university – for ethical and scientific credibility.

Virtually any research that is supported by public or private funds will require oversight by an Institutional Review Board – whether it is commercially operated or at some healthcare organization or university – for ethical and scientific credibility.

Of course, if you are involved in any kind of research – modest or elaborate – you need to ensure that your research methodology meets standards of validity and reliability, otherwise your data will be dismissed as unsound. Nevertheless, conducting a well-designed research project involving human participants is usually very challenging, as the researchers must ensure that at least the following are adequately addressed and satisfied:

Case Management Research and Ethical Standards

| Sample Research-Related Questions Case Managers May Ask to Ensure Adherence to Ethical Standards |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Accommodating these expectations is not simple, which explains why so many research findings are questionable, and why researchers sometimes change aspects of their research design at some point in their data collection when they begin to encounter problems.

If you are interested in conducting research – which is much needed to continue to persuade the public and potential consumers of case management’s credibility and worth – you would do well to enlist experienced and well-published researchers as advisors.

Commencing a good research program is often like starting a business in which unanticipated problems seem to chronically appear. Knowing where to go for counsel has saved many a project from disaster or oblivion.

Commencing a good research program is often like starting a business in which unanticipated problems seem to chronically appear. Knowing where to go for counsel has saved many a project from disaster or oblivion.

The old adage of “Just do the right thing” has some value, but it overlooks the fact that many ethical dilemmas can occur in which “doing the right thing” is not at all obvious.

The CCMC standards described in the Code of Professional Conduct can only provide you with reminders and directives that suggest what the “right thing” is. You, nevertheless, have to constantly rely on your experience and ethical reasoning to determine the right course of action.